48 fichiers modifiés avec 1138 ajouts et 24 suppressions

BIN

rapport/30aSnake.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/RelU_vs_Tanh.JPG

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/a_plot.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/ciphar-10.jpeg

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/Logo_Sorbonne_Universite.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/Logo_Sorbonne_Université.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/arts.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/rnn/0.0015245312824845314_1_25_0.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/rnn/0.006223898380994797_3_24_1.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/rnn/164_126_fig2.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/rnn/164_126_fig3.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/rnn/164_126_fig4.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/images/rnn/256_32_fig2.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/RelU_vs_Tanh.JPG

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_sinus.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_ReLU.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_sin.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_snake.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_swish.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_tanh.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_x+sin.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_snake_8neuronne.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_x2_ReLU.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_x2_sin.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_x2_snake.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_x2_swish.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_x2_tanh.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/prediction_x2_x+sin.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/snake_article.JPG

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/img_partie_1/snake_donnee_augente.png

Voir le fichier

+ 355

- 0

rapport/jmlr2e.sty

Voir le fichier

| @@ -0,0 +1,355 @@ | |||

| % | |||

| % File: Macros for Journal of Machine Learning Research | |||

| % Very minor modification of macros for Journal of Artificial | |||

| % Intelligence Research (jair.sty) | |||

| % | |||

| % Suggestions: Submit an issue or pull request to | |||

| % https://github.com/JournalMLR/jmlr-style-file | |||

| % | |||

| % Last edited October 9, 2000 by Leslie Pack Kaelbling | |||

| % Last edited January 23, 2001 by Alex J. Smola (we should set up RCS or CVS) | |||

| % Last edited March 29, 2004 Erik G. Learned-Miller | |||

| % Last edited January 17, 2016 Charles Sutton | |||

| % Last edited January 9, 2017 Charles Sutton | |||

| % (We have now set up GIT, good thing that we waited for it to | |||

| % be invented.) | |||

| % | |||

| % The name of this file should follow the article document | |||

| % type, e.g. \documentstyle[jmlr]{article} | |||

| % Copied and edited from similar file for Machine Learning Journal. | |||

| % Original Author: Jeff Schlimmer | |||

| % Edited by: Kevin Thompson, Martha Del Alto, Helen Stewart, Steve Minton \& Pandu Nayak. | |||

| % Last edited: Mon May 3 20:40:00 1993 by kthompso (Kevin Thompson) on muir | |||

| \typeout{Document Style `jmlr' -- January 2016.} | |||

| \newif\if@abbrvbib\@abbrvbibfalse | |||

| \DeclareOption{abbrvbib}{\@abbrvbibtrue} | |||

| \newif\if@usehyper\@usehypertrue | |||

| \DeclareOption{nohyperref}{\@usehyperfalse} | |||

| \DeclareOption{hyperref}{\@usehypertrue} | |||

| \DeclareOption*{\PackageWarning{jmlr}{Unknown ‘\CurrentOption’}} | |||

| \ProcessOptions\relax | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % REQUIRED PACKAGES | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| \RequirePackage{epsfig} | |||

| \RequirePackage{amssymb} | |||

| \RequirePackage{natbib} | |||

| \RequirePackage{graphicx} | |||

| \if@usehyper | |||

| \RequirePackage[colorlinks=false,allbordercolors={1 1 1}]{hyperref} | |||

| \fi | |||

| \if@abbrvbib | |||

| \bibliographystyle{abbrvnat} | |||

| \else | |||

| \bibliographystyle{plainnat} | |||

| \fi | |||

| \bibpunct{(}{)}{;}{a}{,}{,} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % P A G E S I Z E | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % Change the overall width of the page. If these parameters are | |||

| % changed, they will require corresponding changes in the | |||

| % maketitle section. | |||

| % | |||

| \renewcommand{\topfraction}{0.95} % let figure take up nearly whole page | |||

| \renewcommand{\textfraction}{0.05} % let figure take up nearly whole page | |||

| % Specify the dimensions of each page | |||

| \oddsidemargin .25in % Note \oddsidemargin = \evensidemargin | |||

| \evensidemargin .25in | |||

| \marginparwidth 0.07 true in | |||

| %\marginparwidth 0.75 true in | |||

| %\topmargin 0 true pt % Nominal distance from top of page to top of | |||

| %\topmargin 0.125in | |||

| \topmargin -0.5in | |||

| \addtolength{\headsep}{0.25in} | |||

| \textheight 8.5 true in % Height of text (including footnotes & figures) | |||

| \textwidth 6.0 true in % Width of text line. | |||

| \widowpenalty=10000 | |||

| \clubpenalty=10000 | |||

| \@twosidetrue \@mparswitchtrue \def\ds@draft{\overfullrule 5pt} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % S E C T I O N S | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % Definitions for nicer (?) sections, etc., ideas from Pat Langley. | |||

| % Numbering for sections, etc. is taken care of automatically. | |||

| \def\@startsiction#1#2#3#4#5#6{\if@noskipsec \leavevmode \fi | |||

| \par \@tempskipa #4\relax | |||

| \@afterindenttrue | |||

| \ifdim \@tempskipa <\z@ \@tempskipa -\@tempskipa \@afterindentfalse\fi | |||

| \if@nobreak \everypar{}\else | |||

| \addpenalty{\@secpenalty}\addvspace{\@tempskipa}\fi \@ifstar | |||

| {\@ssect{#3}{#4}{#5}{#6}}{\@dblarg{\@sict{#1}{#2}{#3}{#4}{#5}{#6}}}} | |||

| \def\@sict#1#2#3#4#5#6[#7]#8{\ifnum #2>\c@secnumdepth | |||

| \def\@svsec{}\else | |||

| \refstepcounter{#1}\edef\@svsec{\csname the#1\endcsname}\fi | |||

| \@tempskipa #5\relax | |||

| \ifdim \@tempskipa>\z@ | |||

| \begingroup #6\relax | |||

| \@hangfrom{\hskip #3\relax\@svsec.\hskip 0.1em} | |||

| {\interlinepenalty \@M #8\par} | |||

| \endgroup | |||

| \csname #1mark\endcsname{#7}\addcontentsline | |||

| {toc}{#1}{\ifnum #2>\c@secnumdepth \else | |||

| \protect\numberline{\csname the#1\endcsname}\fi | |||

| #7}\else | |||

| \def\@svsechd{#6\hskip #3\@svsec #8\csname #1mark\endcsname | |||

| {#7}\addcontentsline | |||

| {toc}{#1}{\ifnum #2>\c@secnumdepth \else | |||

| \protect\numberline{\csname the#1\endcsname}\fi | |||

| #7}}\fi | |||

| \@xsect{#5}} | |||

| \def\@sect#1#2#3#4#5#6[#7]#8{\ifnum #2>\c@secnumdepth | |||

| \def\@svsec{}\else | |||

| \refstepcounter{#1}\edef\@svsec{\csname the#1\endcsname\hskip 0.5em }\fi | |||

| \@tempskipa #5\relax | |||

| \ifdim \@tempskipa>\z@ | |||

| \begingroup #6\relax | |||

| \@hangfrom{\hskip #3\relax\@svsec}{\interlinepenalty \@M #8\par} | |||

| \endgroup | |||

| \csname #1mark\endcsname{#7}\addcontentsline | |||

| {toc}{#1}{\ifnum #2>\c@secnumdepth \else | |||

| \protect\numberline{\csname the#1\endcsname}\fi | |||

| #7}\else | |||

| \def\@svsechd{#6\hskip #3\@svsec #8\csname #1mark\endcsname | |||

| {#7}\addcontentsline | |||

| {toc}{#1}{\ifnum #2>\c@secnumdepth \else | |||

| \protect\numberline{\csname the#1\endcsname}\fi | |||

| #7}}\fi | |||

| \@xsect{#5}} | |||

| \def\thesection {\arabic{section}} | |||

| \def\thesubsection {\thesection.\arabic{subsection}} | |||

| \def\section{\@startsiction{section}{1}{\z@}{-0.24in}{0.10in} | |||

| {\large\bf\raggedright}} | |||

| \def\subsection{\@startsection{subsection}{2}{\z@}{-0.20in}{0.08in} | |||

| {\normalsize\bf\raggedright}} | |||

| \def\subsubsection{\@startsection{subsubsection}{3}{\z@}{-0.18in}{0.08in} | |||

| {\normalsize\sc\raggedright}} | |||

| \def\paragraph{\@startsiction{paragraph}{4}{\z@}{1.5ex plus | |||

| 0.5ex minus .2ex}{-1em}{\normalsize\bf}} | |||

| \def\subparagraph{\@startsiction{subparagraph}{5}{\z@}{1.5ex plus | |||

| 0.5ex minus .2ex}{-1em}{\normalsize\bf}} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % F O O T N O T E S | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % Change the size of the footnote rule | |||

| % | |||

| % \renewcommand{\footnoterule}{\vspace{10pt}\hrule width 0mm} | |||

| \long\def\@makefntext#1{\@setpar{\@@par\@tempdima \hsize | |||

| \advance\@tempdima-15pt\parshape \@ne 15pt \@tempdima}\par | |||

| \parindent 2em\noindent \hbox to \z@{\hss{\@thefnmark}. \hfil}#1} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % A B S T R A C T | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| %% use \begin{abstract} .. \end{abstract} for abstracts. | |||

| \renewenvironment{abstract} | |||

| {\centerline{\large\bf Abstract}\vspace{0.7ex}% | |||

| \bgroup\leftskip 20pt\rightskip 20pt\small\noindent\ignorespaces}% | |||

| {\par\egroup\vskip 0.25ex} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % KEYWORDS | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| %% use \begin{keywords} .. \end{keywords} for keywordss. | |||

| \newenvironment{keywords} | |||

| {\bgroup\leftskip 20pt\rightskip 20pt \small\noindent{\bf Keywords:} }% | |||

| {\par\egroup\vskip 0.25ex} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % FIRST PAGE, TITLE, AUTHOR | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % Author information can be set in various styles: | |||

| % For several authors from the same institution: | |||

| % \author{Author 1 \and ... \and Author n \\ | |||

| % \addr{Address line} \\ ... \\ \addr{Address line}} | |||

| % if the names do not fit well on one line use | |||

| % Author 1 \\ {\bf Author 2} \\ ... \\ {\bf Author n} \\ | |||

| % To start a seperate ``row'' of authors use \AND, as in | |||

| % \author{Author 1 \\ \addr{Address line} \\ ... \\ \addr{Address line} | |||

| % \AND | |||

| % Author 2 \\ \addr{Address line} \\ ... \\ \addr{Address line} \And | |||

| % Author 3 \\ \addr{Address line} \\ ... \\ \addr{Address line}} | |||

| % Title stuff, borrowed in part from aaai92.sty | |||

| \newlength\aftertitskip \newlength\beforetitskip | |||

| \newlength\interauthorskip \newlength\aftermaketitskip | |||

| %% Changeable parameters. | |||

| \setlength\aftertitskip{0.1in plus 0.2in minus 0.2in} | |||

| \setlength\beforetitskip{0.05in plus 0.08in minus 0.08in} | |||

| \setlength\interauthorskip{0.08in plus 0.1in minus 0.1in} | |||

| \setlength\aftermaketitskip{0.3in plus 0.1in minus 0.1in} | |||

| %% overall definition of maketitle, @maketitle does the real work | |||

| \def\maketitle{\par | |||

| \begingroup | |||

| \def\thefootnote{\fnsymbol{footnote}} | |||

| \def\@makefnmark{\hbox to 0pt{$^{\@thefnmark}$\hss}} | |||

| \@maketitle \@thanks | |||

| \endgroup | |||

| \setcounter{footnote}{0} | |||

| \let\maketitle\relax \let\@maketitle\relax | |||

| \gdef\@thanks{}\gdef\@author{}\gdef\@title{}\let\thanks\relax} | |||

| \def\@startauthor{\noindent \normalsize\bf} | |||

| \def\@endauthor{} | |||

| \def\@starteditor{\noindent \small {\bf Editor:~}} | |||

| \def\@endeditor{\normalsize} | |||

| \def\@maketitle{\vbox{\hsize\textwidth | |||

| \linewidth\hsize \vskip \beforetitskip | |||

| {\begin{center} \Large\bf \@title \par \end{center}} \vskip \aftertitskip | |||

| {\def\and{\unskip\enspace{\rm and}\enspace}% | |||

| \def\addr{\small\it}% | |||

| \def\email{\hfill\small\sc}% | |||

| \def\name{\normalsize\bf}% | |||

| \def\AND{\@endauthor\rm\hss \vskip \interauthorskip \@startauthor} | |||

| \@startauthor \@author \@endauthor} | |||

| \vskip \aftermaketitskip | |||

| \noindent \@starteditor \@editor \@endeditor | |||

| \vskip \aftermaketitskip | |||

| }} | |||

| \def\editor#1{\gdef\@editor{#1}} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| %%% | |||

| %%% Pagestyle | |||

| %% | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| %% Defines the pagestyle for the title page. | |||

| %% Usage: \jmlrheading{1}{1993}{1-15}{8/93}{9/93}{14-115}{Jane Q. Public and A. U. Thor} | |||

| %% \jmlrheading{vol}{year}{pages}{Submitted date}{published date}{paper id}{authors} | |||

| %% | |||

| %% If your paper required revisions that were reviewed by the action editor, then indicate | |||

| %% this by, e.g. | |||

| %% \jmlrheading{1}{1993}{1-15}{8/93; Revised 10/93}{12/93}{14-115}{Jane Q. Public and A. U. Thor} | |||

| \def\firstpageno#1{\setcounter{page}{#1}} | |||

| \def\jmlrheading#1#2#3#4#5#6#7{\def\ps@jmlrtps{\let\@mkboth\@gobbletwo% | |||

| \def\@oddhead{\scriptsize Journal of Machine Learning Research #1 (#2) #3 \hfill Submitted #4; Published #5}% | |||

| \def\@oddfoot{\parbox[t]{\textwidth}{\raggedright \scriptsize \copyright #2 #7.\\[5pt] | |||

| License: CC-BY 4.0, see \url{https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/}. Attribution requirements | |||

| are provided at \url{http://jmlr.org/papers/v#1/#6.html}.\hfill}}% | |||

| \def\@evenhead{}\def\@evenfoot{}}% | |||

| \thispagestyle{jmlrtps}} | |||

| %% Defines the pagestyle for the rest of the pages | |||

| %% Usage: \ShortHeadings{Minimizing Conflicts}{Minton et al} | |||

| %% \ShortHeadings{short title}{short authors} | |||

| \def\ShortHeadings#1#2{\def\ps@jmlrps{\let\@mkboth\@gobbletwo% | |||

| \def\@oddhead{\hfill {\small\sc #1} \hfill}% | |||

| \def\@oddfoot{\hfill \small\rm \thepage \hfill}% | |||

| \def\@evenhead{\hfill {\small\sc #2} \hfill}% | |||

| \def\@evenfoot{\hfill \small\rm \thepage \hfill}}% | |||

| \pagestyle{jmlrps}} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % MISCELLANY | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % Define macros for figure captions and table titles | |||

| % Figurecaption prints the caption title flush left. | |||

| % \def\figurecaption#1#2{\noindent\hangindent 42pt | |||

| % \hbox to 36pt {\sl #1 \hfil} | |||

| % \ignorespaces #2} | |||

| % \def\figurecaption#1#2{\noindent\hangindent 46pt | |||

| % \hbox to 41pt {\small\sl #1 \hfil} | |||

| % \ignorespaces {\small #2}} | |||

| \def\figurecaption#1#2{\noindent\hangindent 40pt | |||

| \hbox to 36pt {\small\sl #1 \hfil} | |||

| \ignorespaces {\small #2}} | |||

| % Figurecenter prints the caption title centered. | |||

| \def\figurecenter#1#2{\centerline{{\sl #1} #2}} | |||

| \def\figurecenter#1#2{\centerline{{\small\sl #1} {\small #2}}} | |||

| % | |||

| % Allow ``hanging indents'' in long captions | |||

| % | |||

| \long\def\@makecaption#1#2{ | |||

| \vskip 10pt | |||

| \setbox\@tempboxa\hbox{#1: #2} | |||

| \ifdim \wd\@tempboxa >\hsize % IF longer than one line: | |||

| \begin{list}{#1:}{ | |||

| \settowidth{\labelwidth}{#1:} | |||

| \setlength{\leftmargin}{\labelwidth} | |||

| \addtolength{\leftmargin}{\labelsep} | |||

| }\item #2 \end{list}\par % Output in quote mode | |||

| \else % ELSE center. | |||

| \hbox to\hsize{\hfil\box\@tempboxa\hfil} | |||

| \fi} | |||

| % Define strut macros for skipping spaces above and below text in a | |||

| % tabular environment. | |||

| \def\abovestrut#1{\rule[0in]{0in}{#1}\ignorespaces} | |||

| \def\belowstrut#1{\rule[-#1]{0in}{#1}\ignorespaces} | |||

| % Acknowledgments | |||

| \long\def\acks#1{\vskip 0.3in\noindent{\large\bf Acknowledgments}\vskip 0.2in | |||

| \noindent #1} | |||

| % Research Note | |||

| \long\def\researchnote#1{\noindent {\LARGE\it Research Note} #1} | |||

| \renewcommand{\appendix}{\par | |||

| \setcounter{section}{0} | |||

| \setcounter{subsection}{0} | |||

| \def\thesection{\Alph{section}} | |||

| \def\section{\@ifnextchar*{\@startsiction{section}{1}{\z@}{-0.24in}{0.10in}% | |||

| {\large\bf\raggedright}}% | |||

| {\@startsiction{section}{1}{\z@}{-0.24in}{0.10in} | |||

| {\large\bf\raggedright Appendix\ }}}} | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| % PROOF, THEOREM, and FRIENDS | |||

| %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% | |||

| \newcommand{\BlackBox}{\rule{1.5ex}{1.5ex}} % end of proof | |||

| \newenvironment{proof}{\par\noindent{\bf Proof\ }}{\hfill\BlackBox\\[2mm]} | |||

| \newtheorem{example}{Example} | |||

| \newtheorem{theorem}{Theorem} | |||

| \newtheorem{lemma}[theorem]{Lemma} | |||

| \newtheorem{proposition}[theorem]{Proposition} | |||

| \newtheorem{remark}[theorem]{Remark} | |||

| \newtheorem{corollary}[theorem]{Corollary} | |||

| \newtheorem{definition}[theorem]{Definition} | |||

| \newtheorem{conjecture}[theorem]{Conjecture} | |||

| \newtheorem{axiom}[theorem]{Axiom} | |||

+ 4

- 1

rapport/makefile

Voir le fichier

| @@ -3,4 +3,7 @@ all : | |||

| bibtex rapport | |||

| pdflatex rapport.tex | |||

| pdflatex rapport.tex | |||

| rm -f *.blg *.bbl *.aux *.fls *.log *.toc *.fdb_latexmk | |||

| pdflatex presentation.tex | |||

| pdflatex presentation.tex | |||

| rm -f *.blg *.bbl *.aux *.fls *.log *.toc *.fdb_latexmk *.out *.snm | |||

BIN

rapport/prediction_x2_snake_v2.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/prediction_x2_x+sin.png

Voir le fichier

+ 53

- 0

rapport/presentation.nav

Voir le fichier

| @@ -0,0 +1,53 @@ | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {0}{0}{1}{1/1}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {1}{1}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@sectionpages {1}{1}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@subsectionpages {1}{1}} | |||

| \headcommand {\sectionentry {1}{Introduction}{2}{Introduction}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {1}{0}{1}{2/2}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {2}{2}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@sectionpages {2}{2}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@subsectionpages {2}{2}} | |||

| \headcommand {\sectionentry {2}{Classical activation function}{3}{Classical activation function}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {2}{0}{1}{3/3}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {3}{3}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {2}{0}{2}{4/4}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {4}{4}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {2}{0}{3}{5/5}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {5}{5}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {2}{0}{4}{6/6}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {6}{6}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {2}{0}{5}{7/7}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {7}{7}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@sectionpages {3}{7}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@subsectionpages {3}{7}} | |||

| \headcommand {\sectionentry {3}{Ciphar-10}{8}{Ciphar-10}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {3}{0}{1}{8/8}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {8}{8}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {3}{0}{2}{9/9}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {9}{9}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {3}{0}{3}{10/10}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {10}{10}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@sectionpages {8}{10}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@subsectionpages {8}{10}} | |||

| \headcommand {\sectionentry {4}{Wilshire 5000}{11}{Wilshire 5000}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {4}{0}{1}{11/11}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {11}{11}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {4}{0}{2}{12/12}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {12}{12}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@sectionpages {11}{12}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@subsectionpages {11}{12}} | |||

| \headcommand {\sectionentry {5}{LSTM}{13}{LSTM}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {5}{0}{1}{13/13}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {13}{13}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {5}{0}{2}{14/14}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {14}{14}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@sectionpages {13}{14}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@subsectionpages {13}{14}} | |||

| \headcommand {\sectionentry {6}{Conclusion}{15}{Conclusion}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\slideentry {6}{0}{1}{15/15}{}{0}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@framepages {15}{15}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@partpages {1}{15}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@subsectionpages {15}{15}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@sectionpages {15}{15}} | |||

| \headcommand {\beamer@documentpages {15}} | |||

| \headcommand {\gdef \inserttotalframenumber {15}} | |||

BIN

rapport/presentation.pdf

Voir le fichier

+ 262

- 0

rapport/presentation.tex

Voir le fichier

| @@ -0,0 +1,262 @@ | |||

| \documentclass{beamer} | |||

| %Information to be included in the title page: | |||

| \title{Project of Advanced Machine Learning :\\Neural Networks Fail to Learn Periodic Functions\\and How to Fix It} | |||

| \author{Virgile Batto, Émilien Marolleau, Doriand Petit, Émile Siboulet} | |||

| \institute{Machine Learning Avancé (2021-2022)} | |||

| \date{2021} | |||

| \usetheme{Darmstadt} | |||

| \usepackage{amssymb,amsmath,epsfig} | |||

| \usepackage{caption} | |||

| \usepackage{subcaption} | |||

| \DeclareMathOperator{\relu}{relu} | |||

| \DeclareMathOperator{\snake}{snake} | |||

| \logo{ | |||

| \includegraphics[width=2.5cm]{images/Logo_Sorbonne_Universite.png} | |||

| } | |||

| \begin{document} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \maketitle | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \section{Introduction} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{block}{Fonction d'activation snake} | |||

| $$snake_a(x) = x +\frac{1}{a} \sin^2(ax)$$ | |||

| \end{block} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.4\textwidth]{snake_plot.PNG} | |||

| \caption{Tracé des fonctions Snake} | |||

| \label{fig:snake_plot} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \section{Classical activation function} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_ReLU.png} | |||

| \caption{ReLU} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_swish.png} | |||

| \caption{swish} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_tanh.png} | |||

| \caption{tanh} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{tanh.png} | |||

| \caption{tanh avec base de données asymétrique} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prediction d'un signal carré avec différentes fonctions d'activations} | |||

| \label{fig:classique_x2} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_ReLU.png} | |||

| \caption{ReLU} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_swish.png} | |||

| \caption{swish} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_tanh.png} | |||

| \caption{tanh} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prediction d'un signal sinus avec différentes fonctions d'activations} | |||

| \label{fig:classique_sinus} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{prediction_x2_snake_v2.png} | |||

| \caption{$\snake(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{prediction_x2_x+sin.png} | |||

| \caption{$x+\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_sin.png} | |||

| \caption{$\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prediction d'un signal carré avec différentes fonctions d'activations} | |||

| \label{fig:custom_carre} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

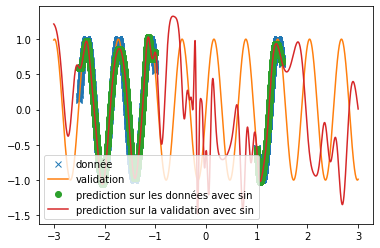

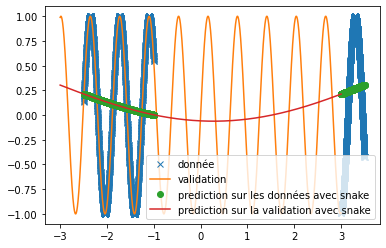

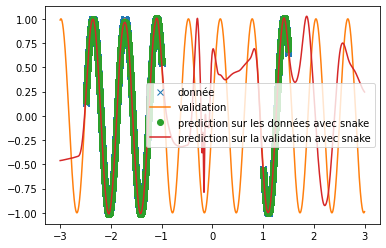

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_snake.png} | |||

| \caption{$\snake(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_sin.png} | |||

| \caption{$x+\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_sin.png} | |||

| \caption{$\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction d'un signal sinus avec les différentes fonctions d'activations} | |||

| \label{fig:custom_sinus} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{sinus_quasi_fonctionnelle.png} | |||

| \caption{$\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{snake_quasi_fonctionnelle.png} | |||

| \caption{$\snake(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction par des réseaux de neurones avec des fonctions d'activations périodiques ou pseudo-périodique} | |||

| \label{fig:custom_sinus} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

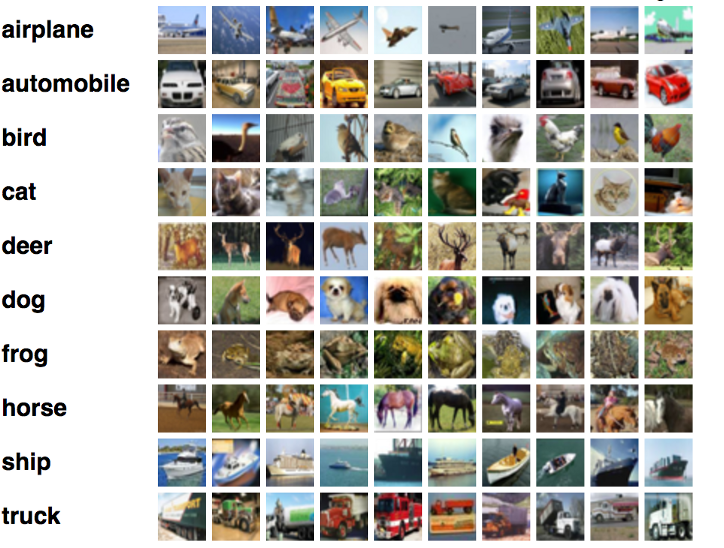

| \section{Ciphar-10} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.8\textwidth]{ciphar-10.jpeg} | |||

| \caption{Exemple de la base de données ciphar-10} | |||

| \label{fig:ciphar-10} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.9\textwidth]{resnet.png} | |||

| \caption{Architecture du réseau de neurone convolutionnel ResNet-18} | |||

| \label{fig:resnet} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.60\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{snake.png} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction de snake (a = 1) sur la base de données Ciphar-10} | |||

| \label{snake_ciphar} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.60\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{reLu.png} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction de ReLu sur la base de données Ciphar-10} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Comparaison de l'efficacité de Snake\\ par rapport à ReLu sur un tache de classification d'image} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

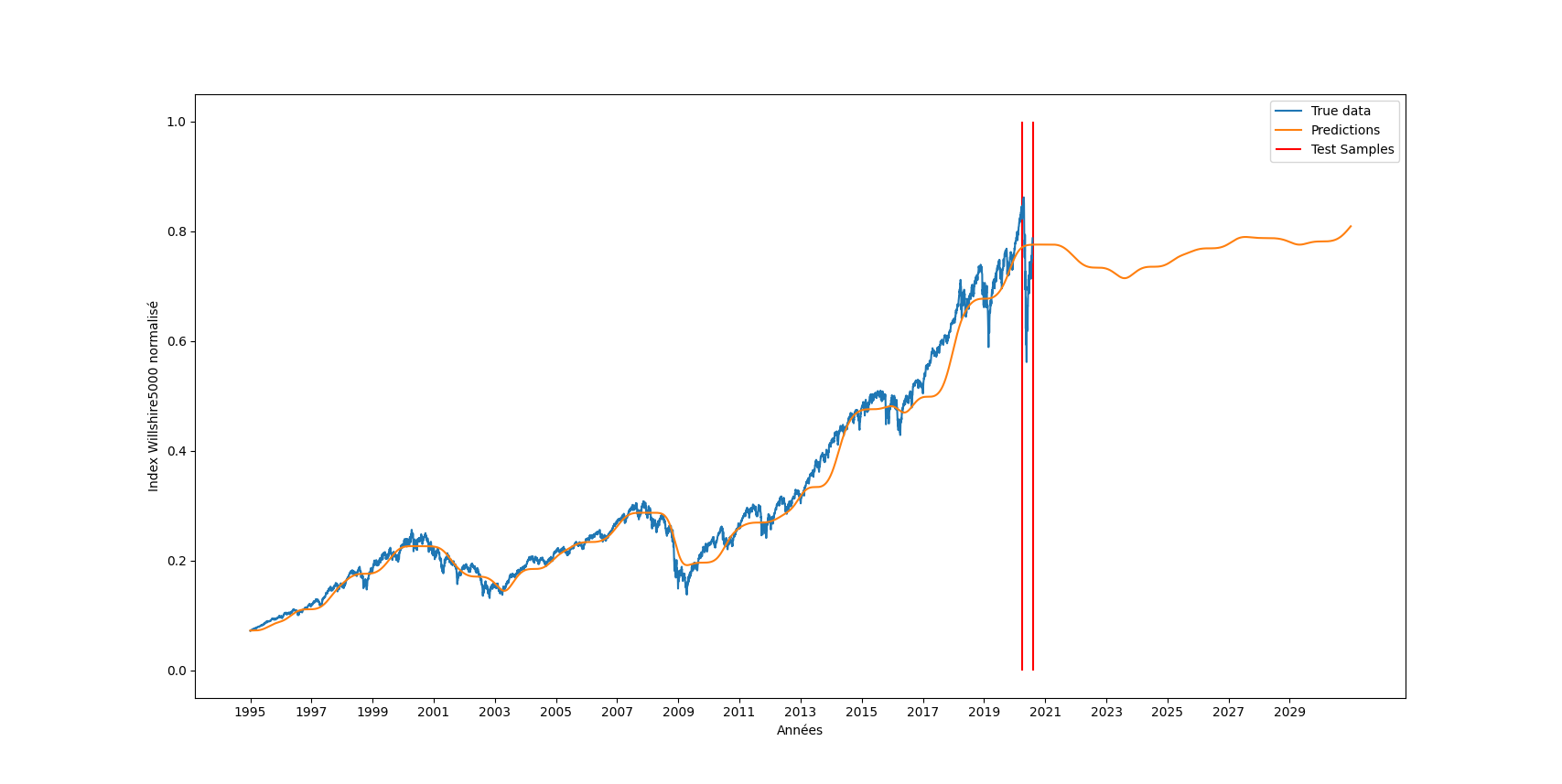

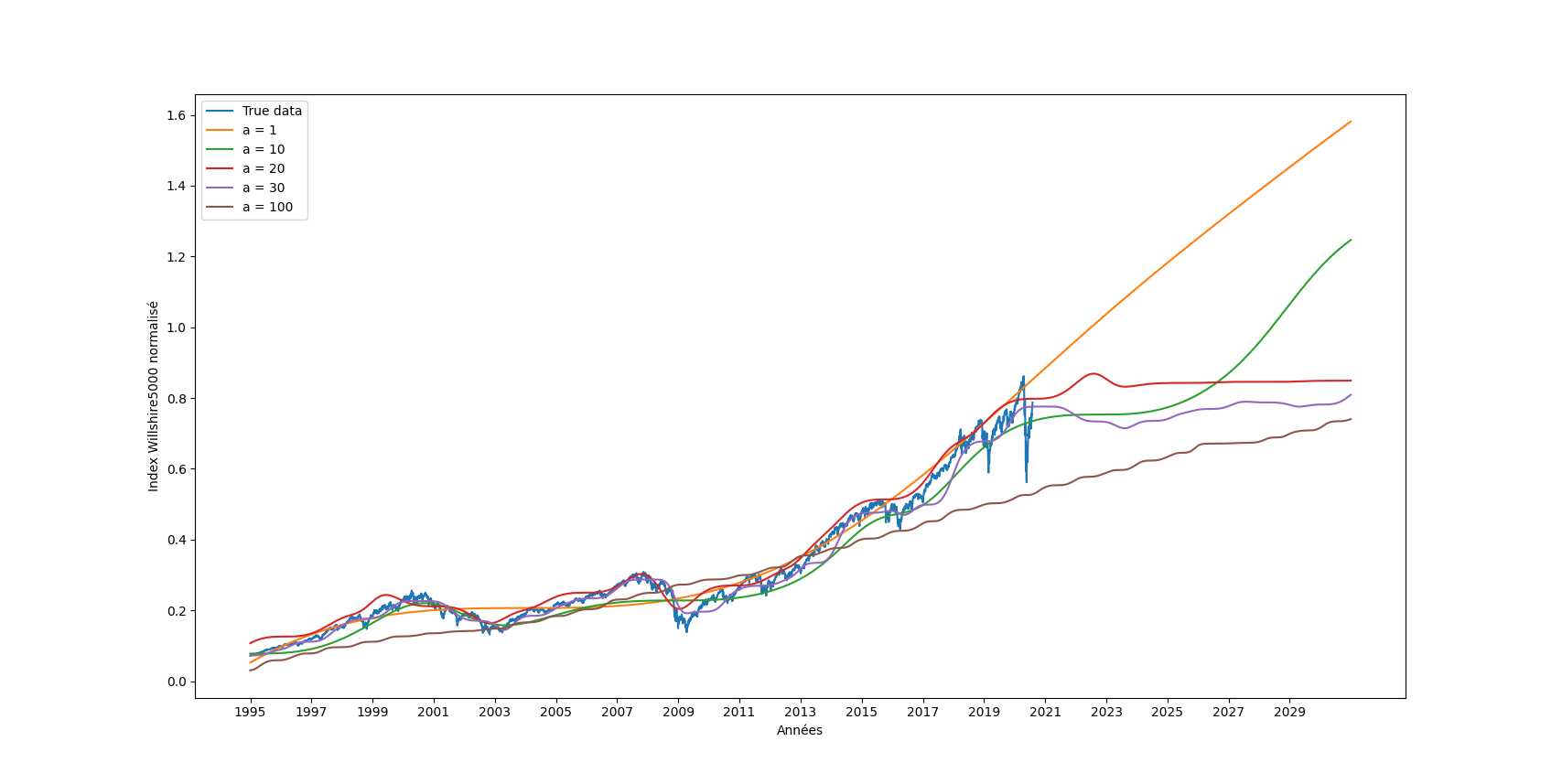

| \section{Wilshire 5000} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 1\textwidth]{a_plot.png} | |||

| \caption{Prédictions pour différentes valeurs de a} | |||

| \label{fig:snake_plot} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 1\textwidth]{30aSnake.png} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction pour a = 30} | |||

| \label{fig:snake_plot} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \section{LSTM} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{images/rnn/164_126_fig2.png} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction des températures par réseau récurent} | |||

| \label{meteornn1} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.40\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{images/rnn/164_126_fig4.png} | |||

| \caption{Vérificaiton de la staibilité de la prédiction} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction par des réseaux utilisant des couches LSTM} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.8\textwidth]{images/rnn/256_32_fig2.png} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction de l'évolution du wilshire5000} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \section{Conclusion} | |||

| \begin{frame} | |||

| \begin{center} | |||

| \Huge{ Merci pour votre attention !} | |||

| \end{center} | |||

| \end{frame} | |||

| \end{document} | |||

+ 33

- 0

rapport/rapport.bib

Voir le fichier

| @@ -12,4 +12,37 @@ | |||

| timestamp = {Wed, 17 Jun 2020 14:28:54 +0200}, | |||

| biburl = {https://dblp.org/rec/journals/corr/abs-2006-08195.bib}, | |||

| bibsource = {dblp computer science bibliography, https://dblp.org} | |||

| } | |||

| @inproceedings{avion, | |||

| author = {Deng, Tuo and Cheng, Aijie and Han, Wei and Lin, Hai}, | |||

| year = {2019}, | |||

| month = {02}, | |||

| pages = {}, | |||

| title = {Visibility Forecast for Airport Operations by LSTM Neural Network}, | |||

| doi = {10.5220/0007308204660473} | |||

| } | |||

| @Article{covid19, | |||

| author={Sunder, Shyam}, | |||

| title={How did the U.S. stock market recover from the Covid-19 contagion?}, | |||

| journal={Mind {\&} Society}, | |||

| year={2021}, | |||

| month={Nov}, | |||

| day={01}, | |||

| volume={20}, | |||

| number={2}, | |||

| pages={261-263}, | |||

| issn={1860-1839}, | |||

| doi={10.1007/s11299-020-00238-0}, | |||

| url={https://doi.org/10.1007/s11299-020-00238-0} | |||

| } | |||

| @misc{agrawal2019machine, | |||

| title={Machine Learning for Precipitation Nowcasting from Radar Images}, | |||

| author={Shreya Agrawal and Luke Barrington and Carla Bromberg and John Burge and Cenk Gazen and Jason Hickey}, | |||

| year={2019}, | |||

| eprint={1912.12132}, | |||

| archivePrefix={arXiv}, | |||

| primaryClass={cs.CV} | |||

| } | |||

BIN

rapport/rapport.pdf

Voir le fichier

+ 431

- 23

rapport/rapport.tex

Voir le fichier

| @@ -1,48 +1,456 @@ | |||

| \documentclass[french]{article} | |||

| \documentclass{article} | |||

| \usepackage{jmlr2e} | |||

| \usepackage{natbib} | |||

| \usepackage{hyperref} | |||

| \usepackage{amssymb,amsmath,epsfig} | |||

| \usepackage{caption} | |||

| \usepackage{subcaption} | |||

| \usepackage{geometry,fancyhdr} | |||

| \usepackage{graphicx} | |||

| \usepackage[utf8]{inputenc} | |||

| \usepackage[french,english]{babel} | |||

| \usepackage[T1]{fontenc} | |||

| \usepackage{babel} | |||

| \usepackage{amsmath} | |||

| \usepackage{graphicx} | |||

| \usepackage{ulem} | |||

| \usepackage{cancel} | |||

| \usepackage{amsfonts} | |||

| \usepackage{bbm} | |||

| \usepackage{lipsum} | |||

| \usepackage{float} | |||

| \sloppy | |||

| \usepackage{geometry} | |||

| \geometry{hmargin=2.5cm,vmargin=2.5cm} | |||

| \usepackage{amsmath} | |||

| \DeclareMathOperator{\relu}{relu} | |||

| \DeclareMathOperator{\snake}{snake} | |||

| \title{Project de Machine Learning Avancé :\\Neural Networks Fail to Learn Periodic Functions\\and How to Fix It} | |||

| \author{Virgile Batto, Émilien Marolleau, Doriand Petit, Émile Siboulet} | |||

| \editor{Machine Learning Avancé (2021-2022)} | |||

| \begin{document} | |||

| \title{Project of Advanced Machine Learning :\\Neural Networks Fail to Learn Periodic Functions\\and How to Fix It} | |||

| \author{\name Virgile Batto \email virgile.batto@ens-paris-saclay.fr \\ | |||

| \addr Master Systèmes Avancés et Robotiques \\ | |||

| Sorbonne Université\\ | |||

| Paris, France | |||

| \AND | |||

| \name Émilien Marolleau \email emilien.marolleau@ens-rennes.fr \\ | |||

| \addr Master Ingénierie des Systèmes Intelligents \\ | |||

| Sorbonne Université\\ | |||

| Paris, France | |||

| \AND | |||

| \name Doriand Petit \email doriand.petit@telecom-paris.fr \\ | |||

| \addr Master Ingénierie des Systèmes Intelligents \\ | |||

| Sorbonne Université\\ | |||

| Paris, France | |||

| \AND | |||

| \name Émile Siboulet \email emile.siboulet@ens-paris-saclay.fr \\ | |||

| \addr Master Systèmes Avancés et Robotiques \\ | |||

| Sorbonne Université\\ | |||

| Paris, France} | |||

| \maketitle | |||

| \vfill | |||

| \begin{figure}[h!] | |||

| \begin{abstract} | |||

| Learning periodic or pseudo-periodic functions that will keep interesting behaviors outside the learning domains is impossible by classical activation functions such as $\relu$ or $\tanh$. To solve this problem we can suppose that using non-linear periodic or pseudo-periodic functions would solve the problem. Moreover, the article is supposed to retrieve some classical ability for activation function such as classification task. This is not that simple, indeed multiple properties are needed to match the specifications of an activation function. We will try to reproduce the results obtained in \cite{article_base} which proposes to use the $\snake$ function as an activation function in the deep layers. To do so, we will compare the results of the article by varying the size of the different proposed networks and by comparing the results with other methods allowing to learn periodic or pseudo-periodic evolutions. The results found as a result of this work are less consistent than what was found in the original paper. | |||

| \end{abstract} | |||

| \begin{keywords} | |||

| Pseudo-periodic Functions, Machine Learning , Snake Funciton, Forcasting, Long Short-term Memory | |||

| \end{keywords} | |||

| \section*{Introduction} | |||

| This work is based on the article \cite{article_base} which proposes a method of learning periodic functions to obtain predictions outside the learning range. Following this article, this function will be implemented from this article in Tensorflow and Pytorch. This article is still under revision and has received favorable opinions with reservations on the reproducibility of results \footnote{\url{https://openreview.net/forum?id=ysFCiXtCOj}}. | |||

| \section{Testing of different activation functions on simple data} | |||

| \subsection{The classic activation functions} | |||

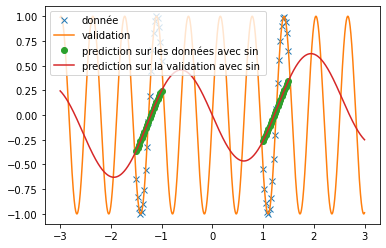

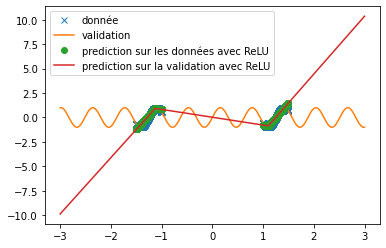

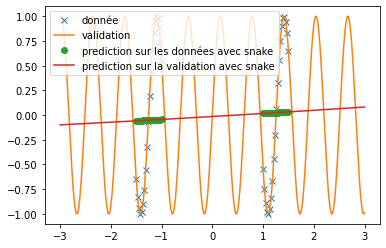

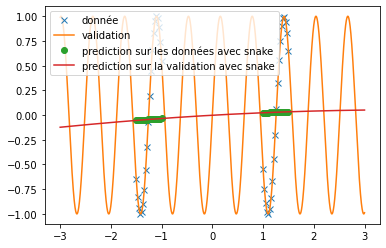

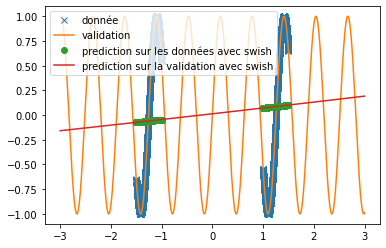

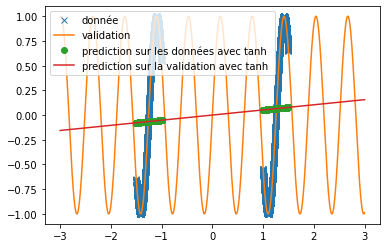

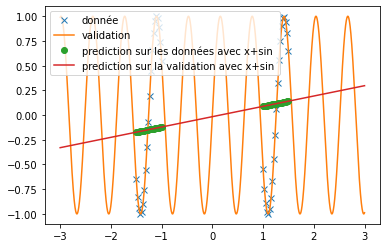

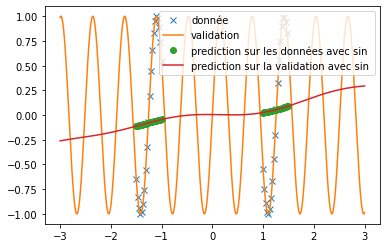

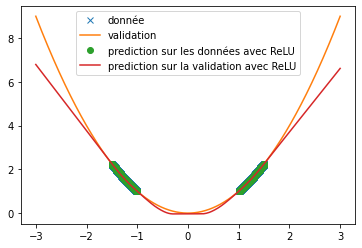

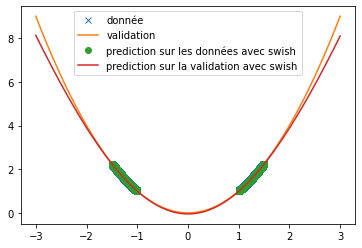

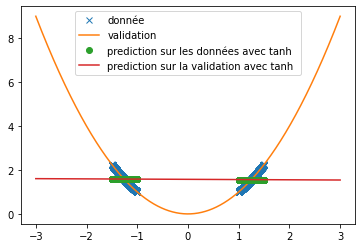

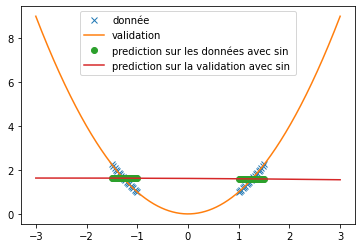

| First, we set up classical activation functions (ReLU, swish and tanh) to predict semi-periodic or periodic signals. To do this we placed ourselves in the same condition as in the article "Neural Networkks Fail to Learn Periodic Function and How to Fix It", i.e. with a single hidden layer neural network of 512 neurons. | |||

| Different functions have been used to verify the ability of the ReLU, tanh and swish functions to predict signals. Here we are particularly interested in the prediction of the sine function and an $x^2$ function. | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_ReLU.png} | |||

| \caption{ReLU} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_swish.png} | |||

| \caption{swish} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_tanh.png} | |||

| \caption{tanh} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prediction of a square wave signal with different activation functions} | |||

| \label{fig:classique_x2} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_ReLU.png} | |||

| \caption{ReLU} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_swish.png} | |||

| \caption{swish} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_tanh.png} | |||

| \caption{tanh} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prediction of a sine signal with different activation functions} | |||

| \label{fig:classique_sinus} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

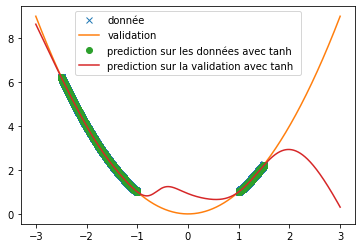

| Thus, we can see that when predicting a square function, tanh gives the mean value of the point cloud while ReLU and swish provide a more accurate approximation (cf fig \ref{fig:classique_x2}) . In addition, the small number of training data taken (in order to be as close as possible to the article) leads to a rather long convergence of the results. Here the training was stopped when the losses stagnated (after about 100 iterations) but it is possible that with a longer training the prediction becomes much better. This may explain the different results of the article since in this one, the activation function tanH gives a more convincing result (cf fig \ref{fig:arti_results}). A similar result is obtained when using a non-symmetric training base (see fig \ref{fig:tanh} ) | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.45\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.5\textwidth]{./images/logo.png} | |||

| \caption{} | |||

| \includegraphics[width = \textwidth]{img_partie_1/RelU_vs_Tanh.JPG} | |||

| \caption{Prediction of Tanh presented by the article} | |||

| \label{fig:arti_results} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.45\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = \textwidth]{tanh.png} | |||

| \caption{Tanh prediction with asymmetric BDD} | |||

| \label{fig:tanh} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \tableofcontents | |||

| \newpage | |||

| However, when predicting a sine, the three functions do not provide relevant results at all (see fig \ref{fig:classique_sinus}). This is due to the small number of points given for training, which prevents the networks from overlearning and tries to force them to make a true prediction. | |||

| Thus, we can see very clearly that in the case of periodic function prediction, the classical activation functions are absolutely irrelevant. We are therefore interested in other activation functions. | |||

| \section{Introduction} | |||

| Ce travail se base sur l'article \cite{article_base} qui porpose une méthode d'apprentissage des fonctions périodique pour obtenir des prédiction hors de la plage d'apprentissage. | |||

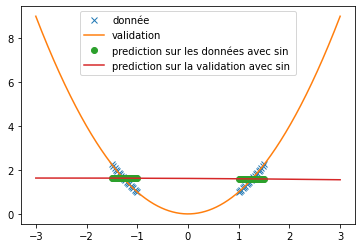

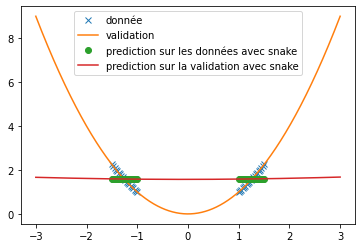

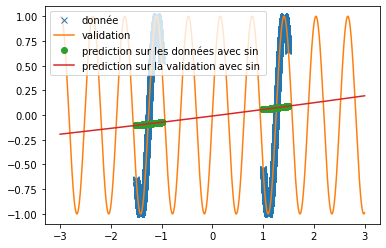

| \subsection{New activation functions} | |||

| A new activation function is implemented: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item the function $x+frac{sin(x)}$. | |||

| \item the function $x+frac{sin(x)}$. | |||

| \item the function $x+frac{sin(x)^2}{\alpha}$ | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| we try it as before on the prediction of sine and the prediction of $x^2$. We use the same conditions as in the article, i.e. a single hidden layer network of 512 neurons and $\alpha=10$. We obtain the following results: | |||

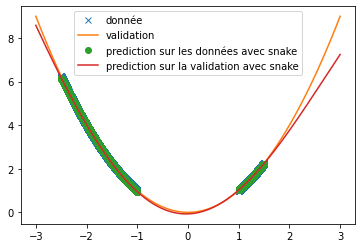

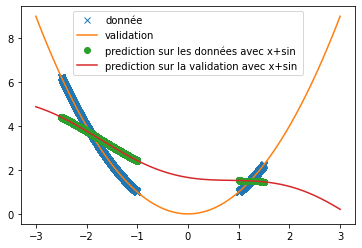

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_snake.png} | |||

| \caption{$\snake(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_x+sin.png} | |||

| \caption{$x+\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_x2_sin.png} | |||

| \caption{$\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prediction of a square with different activation functions} | |||

| \label{fig:custom_carre} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_snake.png} | |||

| \caption{$\snake(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_sin.png} | |||

| \caption{$x+\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus_sin.png} | |||

| \caption{$\sin(x)$} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prediction of a sine signal with different activation functions} | |||

| \label{fig:custom_sinus} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| We can see that, with training bases similar to the one presented in the article and an identical architecture, we do not obtain any coherent result. This is surely due to an extremely long convergence time which means that we never reach a good prediction. The results provided in the article are much more encouraging (cf fig: \ref{fig:articel_snake}). Nevertheless, when using a training base with a higher density of points, we obtain much better results with the snake function, although these are still not relevant for the prediction of a sine: | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.45 \textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = \textwidth]{prediction_x2_snake_v2.png} | |||

| \caption{prediction with snake as activation} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.45 \textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = \textwidth]{img_partie_1/snake_donnee_augente.png} | |||

| \caption{prediction with snake as activation} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

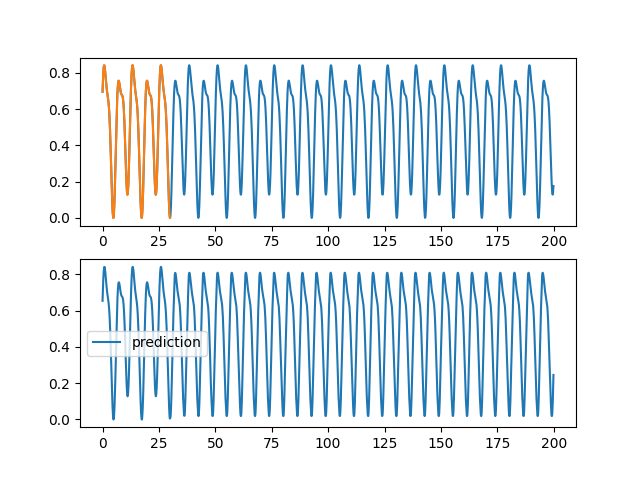

| \subsection{Attempt to make the new activation function work with other network architecture} | |||

| Keeping the same form of training base as in the article (see the points in the figure \ref{fig:articel_snake} ), we change the neural network architectures in order to check if a correct prediction is still possible. We are interested in a classical sine function and we try to predict a sine signal of a different frequency. | |||

| Several tracks are explored: | |||

| \begin{itemize} | |||

| \item the decrease of the number of neurons | |||

| \item the increase in the number of layers | |||

| \end{itemize} | |||

| in a first time we strongly decrease the number of neurons, we only put 4 hidden neurons: | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.5\textwidth]{img_partie_1/prediction_sinus.png} | |||

| \caption{prediction d'un sinus par} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| The results are rather interesting and show that it would be necessary to have a number of data much higher than the number of neurons. | |||

| To solve the frequency problem, we made a network with 5 chained layers of 64 neurons and in order to virtually increase the number of data, we decrease the batch size while increasing the number of iterations. We obtain a rather conclusive result; | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.5\textwidth]{sinus_quasi_fonctionnelle.png} | |||

| \caption{prediction with a hidden multi-layer network} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| We extrapolate these results to the snake activation function, and we use the same architecture, but with more training data and we obtain a result similar to the one presented in the article: | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.5\textwidth]{snake_quasi_fonctionnelle.png} | |||

| \caption{prediction with a hidden multi-layer network with snake in activation function} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| Thus, we obtain the same results as those presented in the article, but using extremely different architecture than those presented in order to overcome the convergence time problem. | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = \textwidth]{img_partie_1/snake_article.JPG} | |||

| \caption{Prediction of a sine with the snake function, from the article studied} | |||

| \label{fig:articel_snake} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \section{Snake / ReLu comparison on the Ciphar-10 training base} | |||

| \subsection{Problem setting} | |||

| This article aims at showing that snake is a reliable alternative to activation functions, so it must be proved that it is as accurate as the others in common machine learning tasks. Indeed the main interest of the snake activation function is to be efficient with periodic and aperiodic functions. Where the other parts of this report focus on the question of prediction on periodic functions, this part allows to find the results of the article announcing that snake competes with other well-known activation functions, like ReLU. Thus, in accordance with the experiments of the article, a classification task has been reproduced on the Ciphar-10 training base. | |||

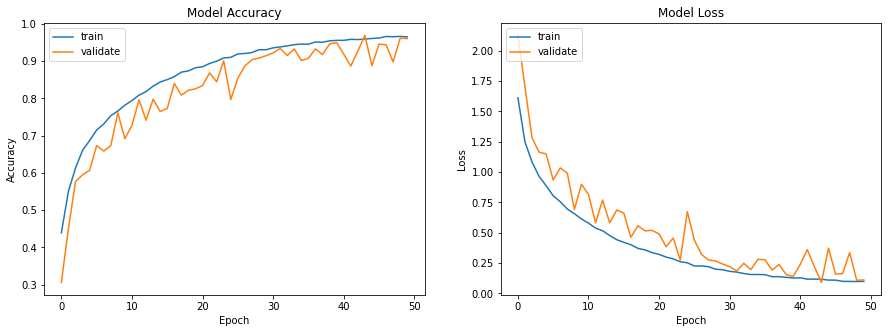

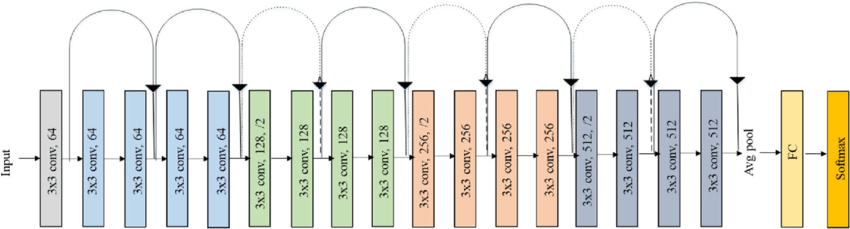

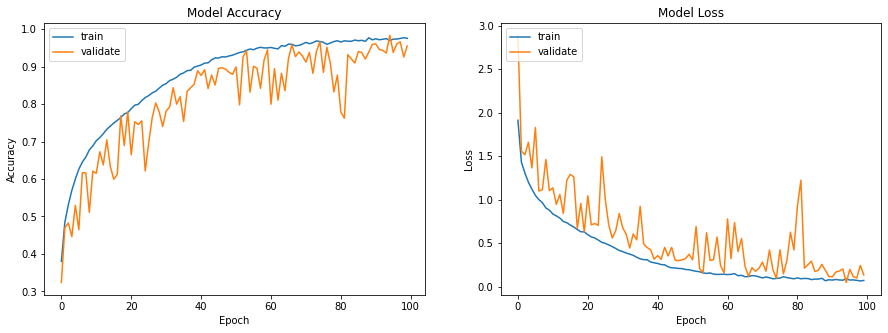

| \subsection{Technical solution and implementation} | |||

| According to the article, Snake manages to reach an accuracy of 93\%. It is comparable to those obtained with other activation functions, especially in classification tasks. Thus to confirm this and in accordance with the article, the classification of images from the Ciphar-10 database has been trained using the convolution network ResNet-18. The representation of its architecture is shown on the figure \ref{fig:resnet}. | |||

| This one is made of convolution layers with a kernel of size 3x3, the size of the convolutions increases with the depth of the layers. Between each layer we add information from the previous layer, tht's why tis architecture is called ResNet (for Residual Network). The code implementing this network is made of 2 python scripts, the first one is object oriented and defines the ResBlock class which composes all the residual convolution network architecture, it also implements a class inheriting from ResBlock which defines the ResNet18 architecture. The second script calls all the tensorflow functions as well as the Ciphar-10 database and the ResNet18 class. | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.9\textwidth]{resnet.png} | |||

| \caption{Architecture of the ResNet-18 residual convolutional neural network} | |||

| \label{fig:resnet} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \subsection{Results obtained and comparisons with the article} | |||

| The training phase was performed with a batch size of 256, the database is composed of 50,000 images, cut into 60\% for training elements, 20\% for validation data and 20\% with test data. As in the article the data were trained on 100 epochs. The computations were run on an Nvidia RTX 3070 graphics card, for a computation time of 16 minutes. In order to compare the performances with a reference activation function the same calculations were performed with the ReLu function too. The results are visible on the figure \ref{fig:ciphar_ReLu} and on the figure \ref{fig:ciphar_snake}. | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.9\textwidth]{reLu.png} | |||

| \caption{Prédiction avec ReLu comme fonction d'activation sur la base d'entraînement Ciphar-10} | |||

| \label{fig:ciphar_ReLu} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.9\textwidth]{snake.png} | |||

| \caption{Prediction with Snake (a = 1) as activation function on the Ciphar-10 training base} | |||

| \label{fig:ciphar_snake} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| As can be seen in the figures below, the training of the network with the snake activation function for 100 epochs reaches 0.9554 where the training with the ReLu function reaches 0.9611 in 50 epochs. We can therefore confirm the ability of Snake to reach the same performance in concrete classification tasks. However, Snake learns more slowly than ReLu. Indeed it took Snake twice as many epochs as Relu to reach the same results. However, the experiments performed here are therefore in good agreement with the results of the article. | |||

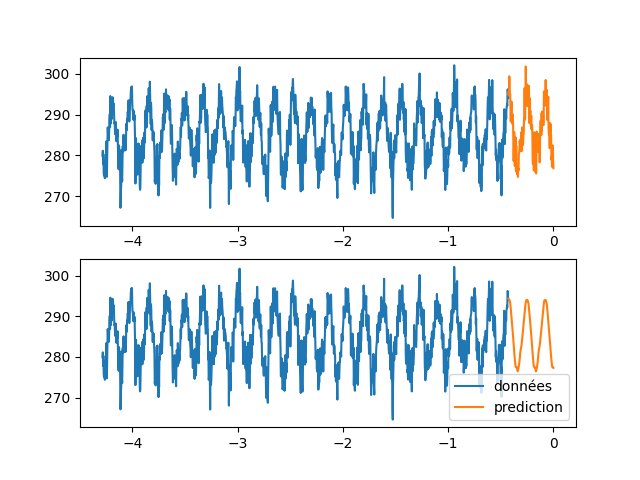

| \section{Financial Data Prediction} | |||

| \subsection{Problem Setting} | |||

| Hence, trying to predict periodic and quasi-periodic functions is not always an easy feat and the use of the Snake activation function can thus be a great help in resolving this issue. Following this idea, it is interesting to focus on another environment : the global economy. Indeed, the total US market capitalization has a quasi-periodic behavior (whether at a microscopic level or a macroscopic one) and the authors thus decided to analyse the snake effect on its predictions. | |||

| \subsection{Data and Pre-processing} | |||

| In order to measure the global economy, the authors decided to use the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Full Cap Index, a common financial index that gives daily samples (on working days exclusively). The dataset is clear and easy to obtain and we thus had no problem in copying the beginning and ending dates of each training and test sets. However, there were some NA values, which come from bank holidays. Rather than dropping them, the first choice was to interpolate their values. However, the paper talked about "around 6300 [training] points in total", while the interpolation gave 6544 points, hence we then decided to remove these interpolations to obtain a satisfying number of points. The only other pre-processing we made was some normalization over the y values, as well as over the x values (which are initially a list from 0 to the number of training points). | |||

| \subsection{Technical Choices} | |||

| According to the paper, we developed a feedforward neural network with 4 hidden layers (1 neuron - 64 neurons - 64 neurons - 1 neurons). The paper specifies the test of several activation functions (ReLU, Swish, sin + cos, sin and Snake). However, it does not precise which layers should have that varying activation function, and after some experiments, it was quite clear that the last layer did not have this special activation (the results with snake chosen for each layer were really bad, while removing the last activation function worked wonders).\\ | |||

| We also chose arbitrarily an SGD optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and a momentum of 0.8.\\ | |||

| Finally, the last choice to be made was about the parameter a of the Snake function. We've noticed an important variation of performances depending on its value, and thus decided to consider this decision as part of the results. | |||

| \subsection{Results and Discussion} | |||

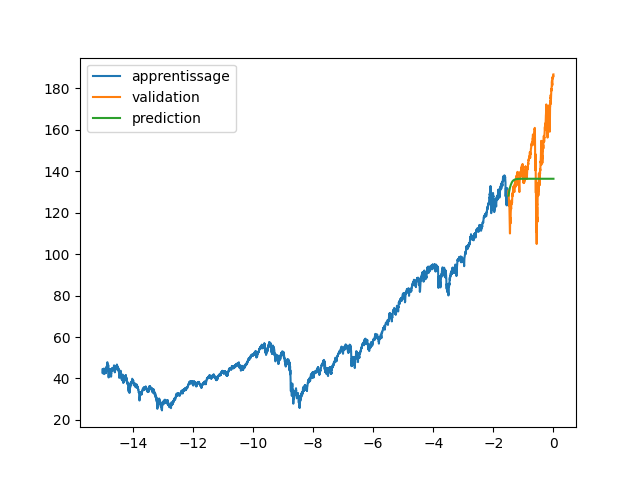

| First of all, we have tried to test which snake parameter gave the best results (figure \ref{fig:wilshire_all_a}). In fact, this choice was dependent on our wish to have a high or a low "frequency" of the resulting quasiperiodic signal. Hence, we have noticed that the choice of the parameter a was crucial in the learning and the prediction of the funciton. A small value of a gave a very low frequency and thus a really important under-fitting. On the other hand, a high a was too difficult to learn as we can see with a value of 100. Finally, for in-between values of a, the choice is ours to make, as we can choose the "degree" of precision we want (do we want to predict the general trend only or do we also want to predict higher-frequency changes). For the rest of this part, we have decided to work with a = 30. | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = \textwidth]{a_plot.png} | |||

| \caption{Predictions of Wilshire5000 for various values of a} | |||

| \label{fig:wilshire_all_a} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| Then, the following goal was to obtain a similar figure and table of the paper with test mean square errors of DNNs using different activation functions, as well as more classical financial models named ARIMA (tab. \ref{tab:results}). Indeed, we were glad to obtain similar trends and magnitudes of result.\\ | |||

| \begin{table*}[] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{tabular}{|c|c|c|c|} | |||

| \hline | |||

| Method & MSE on test set - Our version & MSE on test set - Paper's version & Training Loss \\ \hline | |||

| ARIMA(2, 1, 1) & 0.01605 & 0.0215 +- 0.0075 & - \\ \hline | |||

| ARIMA(2, 2, 1) & 0.01614 & 0.0306 +- 0.0185 & - \\ \hline | |||

| ARIMA(3, 1, 1) & 0.01604 & 0.0282 +- 0.0167 & - \\ \hline | |||

| ARIMA(2, 1, 2) & 0.01602 & 0.0267 +- 0.0154 & - \\ \hline | |||

| ReLU DNN & 0.1205 +- 0.0886 & 0.0113 +- 0.0002 & 0.0330 \\ \hline | |||

| Swish DNN & 0.0119 +- 0.0012 & 0.0161 +- 0.0007 & 0.0012 \\ \hline | |||

| Sin + Cos DNN & 0.0125 +- 0.0019 & 0.0661 +- 0.0936 & 0.0017 \\ \hline | |||

| sin DNN & 0.0118 +- 0.0029 & 0.0236 +- 0.0020 & 0.0019 \\ \hline | |||

| Snake & \textbf{0.0091 +- 0.0012} & \textbf{0.0089 +- 0.0002} & Vanishing \\ \hline | |||

| \end{tabular} | |||

| \caption{Predictions of Wilshire5000 during the test set} | |||

| \label{tab:results} | |||

| \end{table*} | |||

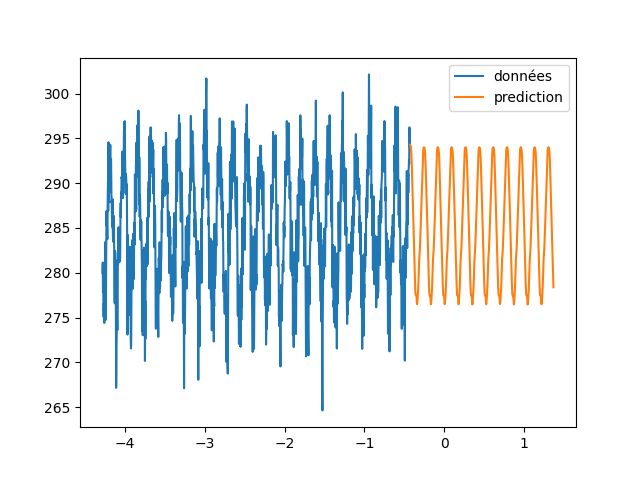

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = \textwidth]{30aSnake.png} | |||

| \caption{Predictions of Wilshire5000 for a = 30} | |||

| \label{fig:wilshire_30a} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| However, we still had some differences with the authors' results. First of all, the ARIMA computations gave quite different results, as their method was left unknown. Ours is deterministic (hence no standard deviation), and the different choices of orders also resulted in similar MSE while the authors had way more various errors. Moreover, we can also notice that, while most of the activation functions results in similar MSE, our Relu DNN has a 10 times higher error. This is quite surprising, and the reason is uncertain. As explained in the next paragraph, the test set's choice might be part of the problem.\\ | |||

| Please note that, while the Snake activation function presented the best results whether in the paper or in our own tests, the author's choice defining the test set is at the very least questionable, if not straight up a bad choice. Indeed, these four months contain the "black thursday", a sudden market crash that cannot be predicted from the training samples, and that was way too quick for our estimated function to follow. Thus, comparing the MSEs on this test set might not be a pertinent indicator. A possible solution would be to modify the test set, but the goal of this project was to obtain the same results as the paper's ones rather than prove the efficiency of their idea. We can nonetheless compare the training loss as it may bring some more informations and we directly notice that, as the authors mentionned, the Snake neural network is the only model which trains to vanishing training loss, only it can learn precisely the entire training range of the indicator. | |||

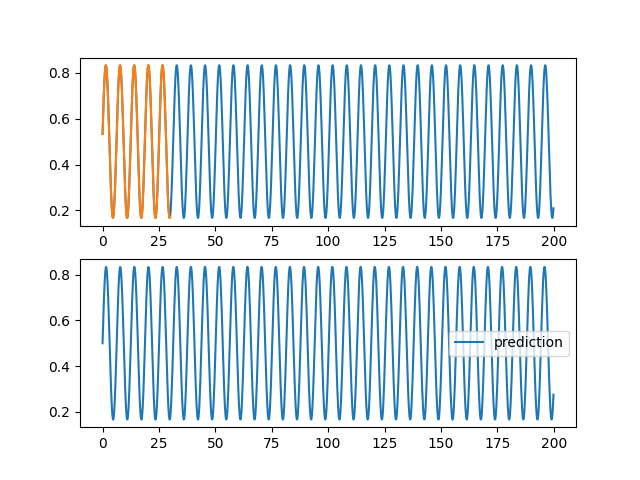

| \section{Use of LSTM layers} | |||

| The most common way to do periodic and pseudoperiodic function prediction is to use LSTMs. This part is only very little developed in the article, however we decided to develop it a little more. This approach allows us to contrast the different results found for prediction. We will approach in particular the case of the Wilshire5000 because the results found by the method of the article are very debatable in view of its evolution (\cite{covid19}). | |||

| %\subsection{Fonction simple} | |||

| %Nous allons tenté de reporduire les résultats des fonctinos simples tel que la somme de sinus. Pour cela on se donne une séquence que l'on fait passer à travers des couches LSTM et dense et l'on tente de prédire la séquence de valeurs décalé d'un pas de temps. Par cette entraînement, le réseaux de neurone apprend à prédire la mesure suivant. En appliquant le réseaux successivement, on est capable de prédire les valeurs suivantes. | |||

| %\begin{figure}[H] | |||

| % \centering | |||

| % \includegraphics[width = 0.4\textwidth]{images/rnn/0.0015245312824845314_1_25_0.png} | |||

| % \caption{Prédictition de la fonction sinus par LSTM} | |||

| %\end{figure} | |||

| %On a obtenu ce résultat en ne donnant que le début de la séquence. | |||

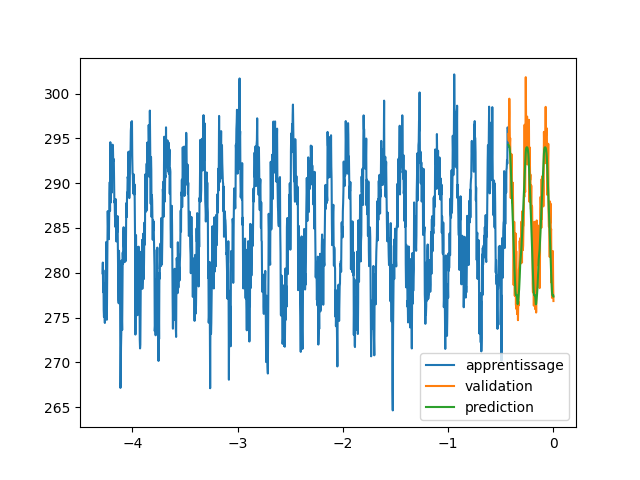

| \subsection{Weather forecasting} | |||

| We will try to predict the average temperature per week of the observatory of Clermont-Ferrand \footnote{\url{https://donneespubliques.meteofrance.fr/?fond=produit&id\_produit=90\&id\_rubrique=32}}. To do this, we give ourselves a series of measurements that we group together by batch so that the neural network is able to predict the next measurement in a sequence. By the capacity of the LSTM layers to be stable by composition one will be able, with a trained network, to apply successively the network to predict the temperatures on a long temporal range (\autoref{meteornn1}).\\ | |||

| \begin{figure} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{images/rnn/164_126_fig2.png} | |||

| \caption{Weather forecasting} | |||

| \label{meteornn1} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{images/rnn/164_126_fig4.png} | |||

| \caption{Verification of the temporal staibility} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \hfill | |||

| \begin{subfigure}[b]{0.3\textwidth} | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{images/rnn/256_32_fig2.png} | |||

| \caption{Wilshire5000} | |||

| \label{wilshire_rnn} | |||

| \end{subfigure} | |||

| \caption{Prediction by networks using LSTM layers} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

| We notice errors relative to the temperature amplitude of the order of $200\%$. This is important but can be explained by the high unpredictability of temperatures. Moreover the fact of taking into account only the data of the station makes the prediction very little precise. A way to treat the problem more globally would be to use convolution layers taking into account the geographical distribution of the different measurements \cite{agrawal2019machine}.\\ | |||

| We also verify the stability in time and the extrapolation of the prediction. We notice that the composition of LSTM is very stable. We can also conclude that there was exploitable knowledge in the weather data. As a matter of fact, we find an oscillatory behavior in a model which does not include a periodic function. | |||

| \subsection{Wilshire5000} | |||

| In this part we will use the same method as in the previous part. Indeed, we are going to constitute sequences from the measurements of the Wilshire5000\footnote{url{https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WILL5000INDFC}} in the hope to predict the following value and to apply it to predict longer sequences. | |||

| We notice that we did not succeed in finding a knowledge in the measurements of wilshire5000(\autoref{wilshire_rnn}). Indeed the solution found by the neural network is to give the value at the previous time step. Moreover, by comparing the evolution of this indicator with what actually happened afterwards (\cite{covid19}), we see that the prediction was quite wrong. The $\snake$ activation functions as well as the LSTMs are not able to predict the evolution of an indicator of the stock market only by its previous evolution. | |||

| \section*{Conclusion} | |||

| We have succeeded in reproducing some of the results of the article. First, we succeeded in showing empirically that the $\snake$ function could be used as an activation function. Then, we showed that it is generally less efficient than the unavoidable $\relu$ function but it allows to learn non-trivial databases such as Ciphar-10.\\ | |||

| Nevertheless, we observed that the parameter $a$ in the snake activation function has a great influence on the prediction. This is a major issue because its arbitrary parameterization strongly impacts the prediction and can lead to false predictions on stock market indicators for instance. LSTM networks are more robust in reproducing periodic and pseudo-periodic functions while remaining stable over time. | |||

| \bibliographystyle{plain} | |||

| \bibliography{rapport} | |||

| \end{document} | |||

| \begin{figure}[h!] | |||

| \begin{figure}[H] | |||

| \centering | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.7\textwidth]{} | |||

| \includegraphics[width = 0.5\textwidth]{} | |||

| \caption{} | |||

| \end{figure} | |||

BIN

rapport/reLu.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/resnet.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/sinus_quasi_fonctionnelle.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/snake.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/snake_donnée_augenté.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/snake_plot.PNG

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/snake_quasi_fonctionnelle.png

Voir le fichier

BIN

rapport/tanh.png

Voir le fichier

Chargement…